Mom, Health Educator,

Fresno County Perinatal Equity Initiative Coordinator

– Gifty

Born and raised in the vibrant and culturally rich country of Ghana, I come from a large, close-knit family, where my grandmother had the joy of bringing ten children into the world. In my family, pregnancies and childbirth have always been celebrated events brimming with excitement and happiness. Growing up, I had the privilege of experiencing these joyous occasions firsthand, which shaped my belief that every childbirth should be a moment of pure bliss.

As I pursued my undergraduate studies, I had the opportunity to travel to rural parts of Ghana for a research project. It was during this time that I encountered an event that would forever change my perspective on childbirth and its associated challenges. In one of the remote communities, I bore witness to a neonatal death — a tragedy that I believe could have been prevented with equal access to healthcare. This devastating loss for the family shattered my heart and challenged my previous notions of the birthing experience.

This heart-rending encounter became etched in my memory, and I couldn’t help but ask myself what role I could play in preventing such tragedies. No pregnancy or childbirth should end in tragedy. Every birthing mother and her family should experience the joy and excitement of having a new life brought into the world. Bringing babies into the world should be a joyous, celebratory season and not a time to mourn.

As someone coming from a developing nation, I was highly aware of the healthcare challenges faced by developing nations. However, I never expected to encounter a maternal health crisis in a developed nation like the United States. To my surprise, sadness, and shock, I discovered that the United States struggles with significant maternal health issues, leaving me grappling with the question of how such disparities could exist in a country with advanced healthcare infrastructure. As my concern about this issue grew, I delved deeper into understanding the underlying factors contributing to the crisis. Through research and conversations with people who have experienced the American healthcare system firsthand, I learned that the maternal health crisis in the U.S. is not evenly distributed. Alarmingly, Black women bear the brunt of this burden, facing disproportionately high risks to their health during pregnancy and childbirth.

This realization saddened me deeply and ignited a burning desire within me to make a difference. I found myself time and again asking the question: “How can I be a part of the solution?” With each new piece of information, my determination to contribute to improving maternal health outcomes for Black women grew stronger. It became clear to me that addressing these disparities is not only a matter of healthcare policy but also a matter of social justice. My own experience with childbirth in the United States has been an eye-opening and transformative one. The maternal health crisis affecting Black women in the U.S. is a complex issue that demands attention, empathy, and action. As I continue my journey in the field of healthcare, I am committed to being an advocate for positive change and working tirelessly to ensure that every woman, regardless of her race or background, has access to the quality care she deserves during pregnancy and childbirth.

Recognizing the need to be an active part of the solution, I understood the importance of furthering my education and acquiring in-depth knowledge. Consequently, I enrolled in the master’s in public health program at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. However, before embarking on this academic journey, I needed to save money for school. To achieve this, I secured a position as a unit secretary in the labor and delivery unit of a community hospital in Southern California. This job was deliberately selected to not only help me save money but also provide valuable firsthand experience within the US healthcare system.

As a unit secretary, I was exposed to numerous eye-opening situations. The hospital catered to a diverse community, including immigrants, underserved women, and vulnerable populations. I observed several areas for improvement, such as the prevalence of unnecessary surgical births. One night, a laboring patient was being induced, and suddenly, I was instructed to call the operating room team to prepare the operating room for a C-section. I was surprised when I discovered that the recently induced patient was being prepped for a C-section. I later learned that the doctors had ordered the C-section due to suspected fetal macrosomia (meaning that the baby was larger than average, greater than 8 pounds 13 ounces). However, upon delivery, the baby weighed slightly under 8 pounds, which led me to wonder if the woman could have had a normal vaginal delivery instead of a C-section. I also witnessed several instances where decisions were made without proper communication or consideration for the patients. Many families faced language barriers or lacked the support to ask questions, and some healthcare providers appeared to make decisions based on their convenience rather than the patient’s needs. These experiences fueled my determination to contribute to the solution and positively impact maternal health outcomes.

After graduate school, I had two main goals: starting my own family and building my public health career. In 2015, I was blessed with the birth of my first son, and my husband and I were overjoyed to begin our family journey together. Just around that same time, I applied for a position at the Black Infant Health program in Fresno, but the opening had already been filled. Instead, I was offered a role as a Health Education Specialist for the Tobacco Prevention Program (TPP).

At first, I was a bit hesitant about the role because TPP focuses mostly on policy work, and I was not comfortable navigating complex systems and rules whiles dealing with the bureaucratic nature that comes with policy formulations. But working with the tobacco prevention program turned out to be a blessing. It pushed me out of my comfort zone and gave me the opportunity to develop my policy advocacy skills, and although it often took years to pass new policies, the impact of tobacco-free policies on community health was truly rewarding. After dedicating four years to the tobacco program, a new door opened for me as the Perinatal Equity Initiative Coordinator at the Health Department. Though I had grown to love the tobacco prevention work, the chance to work with the Black and African American community to improve birth outcomes was close to my heart, and I couldn’t turn down the offer. For the past couple of years, I have been fully committed to this role and will continue to strive for progress until we see a positive change in the birth outcomes of our community.

Like other Black women in the U.S., I have encountered health care providers who failed to pay attention or genuinely listen to my concerns. I remember, following the birth of my second child, when a nurse came to help me get out of bed and walk, I stood up, looked at myself in the mirror, and noticed that my lower left abdomen seemed swollen and distended, feeling unusual. Despite expressing my concern to the nurse, she dismissed it, attributing the issue to being only two days post C-section. I reluctantly accepted her explanation. However, by the fifth day, my left side remained uncomfortably swollen and distended. Worried, I asked the nurse to examine me, explaining that my body felt different compared to my first C-section, and something seemed off. After the examination, she assured me that nothing was wrong, and despite my repeated concerns, I was discharged from the hospital.

During my postpartum appointment with my OB/GYN, I reiterated my concerns, emphasizing that my left abdomen felt odd, more swollen or bulging, and heavier than the right side. I was certain that something was wrong and requested imaging to investigate further. My OB/GYN acknowledged that my lower left abdomen looked swollen but attributed it to the C-section and ignored my request for imaging, suggesting that we wait and see how things progress. Nearly six months postpartum, my symptoms persisted, with my left lower abdomen still appearing distended and causing some level of discomfort and pressure. Unfortunately, no one seemed to take my concerns seriously. Then one day, while caring for my baby, I experienced an extremely sharp pain. The intensity of the pain was so severe that I had to be rushed to the emergency room.

In the emergency room, a CT scan was performed, leading to the diagnosis of an incisional hernia with initial signs of incarceration and early strangulation. The doctor clarified that the bulging appearance of my left abdomen I had reported since the C-section was due to an incisional hernia. If not addressed, it could cause the intestine to become trapped, which is precisely what occurred. The doctor cautioned that an untreated incarcerated hernia might progress to strangulation, causing serious complications. Consequently, surgery was advised to repair the hernia, which I underwent. If my concerns had been considered sooner, I may have avoided this painful experience. I cannot understand why some healthcare providers fail to acknowledge and comprehend our concerns, given that we are very familiar with our own bodies. I would genuinely appreciate their active listening and cooperation when it comes to my health. I am thankful to be alive and able to share my story, but the experience could have had a much different ending. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have survived this distressing ordeal.

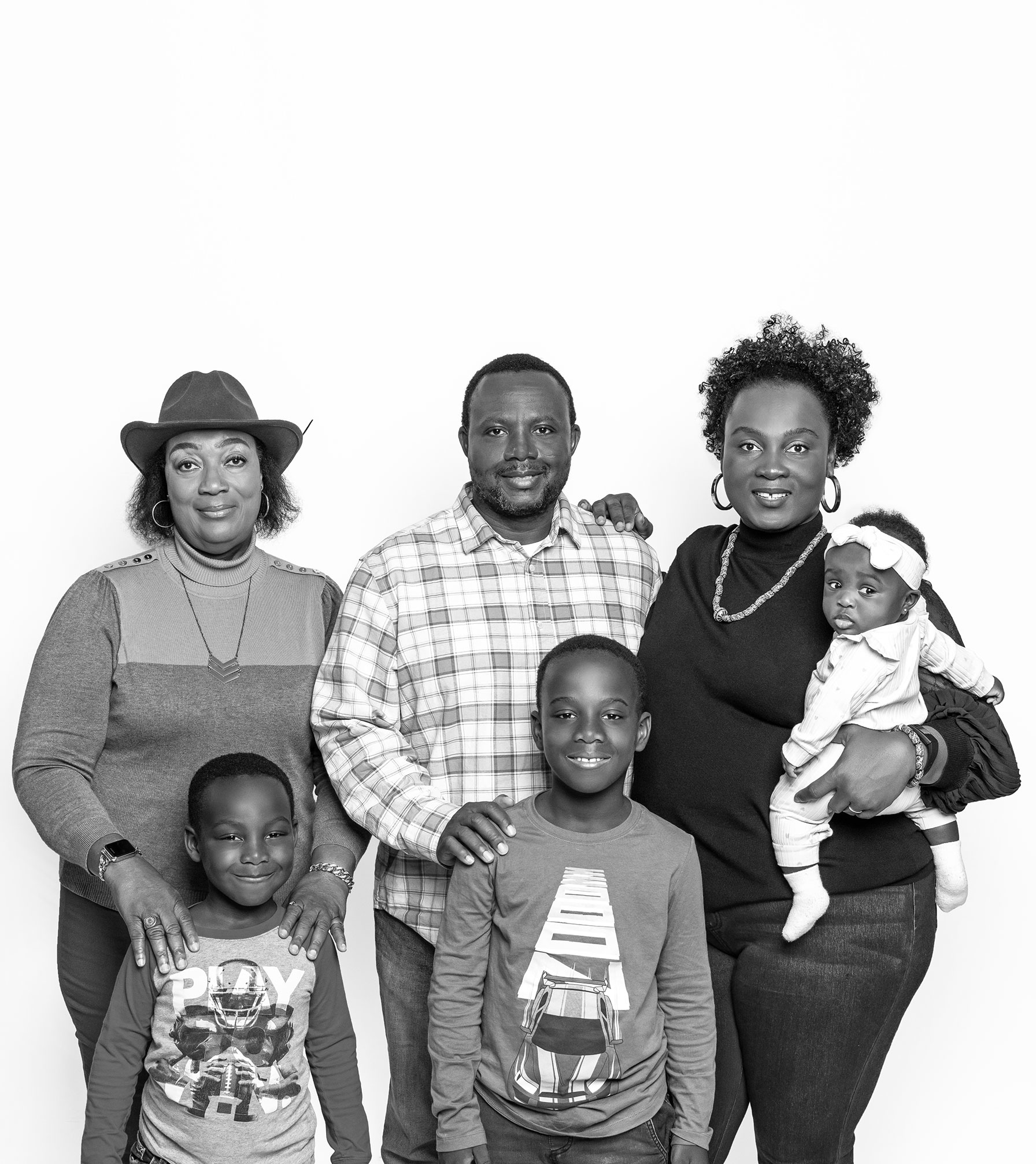

In Fresno, options for expectant mothers are limited. Ideally, there would be a variety of choices available, but the primary option in Fresno is usually a hospital. However, labor and delivery should not be seen exclusively as a medical matter — it should also be recognized as a natural bodily process that may require minimal medical intervention. It would be beneficial for mothers to have access to low-intervention birthing options, such as giving birth in non-hospital settings like birthing centers or at their homes, where the environment is more familiar and comfortable. This would include the availability of water tubs during labor and, importantly, access to doulas who can provide continuous labor support and advocate for the mother’s preferences. Sadly, these options remain scarce in Fresno. I have been fortunate to have my mother stay with me for an extended period during my pregnancies and postpartum periods. I often jokingly refer to her as my unofficial doula. She has truly been my support person, providing emotional and physical assistance to both my husband and I. She took care of everything from making healthy meal choices to looking after my other two young children, allowing me to rest or take a walk. Her empathetic and nonjudgmental listening skills were invaluable. I am incredibly grateful for her unwavering support and thank God for blessing me with such a caring mother.

During my third pregnancy, the first OB/GYN I saw directly suggested that I terminate the pregnancy because of my previous history. While I acknowledged that I was high-risk due to my age and prior complicated pregnancies, I think her approach was not the best. She did not consider or at least respect my decision to continue with the pregnancy. At that moment, I realized I needed to find a new provider who would listen and understand my needs.

Ideally, I wanted a provider who shared my cultural or ethnic background, but unfortunately, Fresno’s medical workforce lacks diversity, particularly regarding Black doctors, nurses, midwives, and doulas. In the end, I chose an OB/GYN who had previously been an engineer before pursuing a career in medicine. His unique life experience, values, and evident passion for his new career in obstetrics and gynecology appealed to me. He stood out not just for the distinctive bowties he wore but also for his ability to genuinely listen and understand my concerns. Unlike my previous OB/GYN, he didn’t question my decision to continue the pregnancy despite my high-risk status. Instead, he adopted a supportive attitude, saying, “Let’s see how far we can get together,” and referred me to specialists who could help monitor my health. He accepted me as I was and provided me with valuable resources. Everyone should have a doctor like him — one who embraces patients as they are and works alongside them.

Fresno County experiences some of the worst birth outcomes, indicating a need for long-term changes to address this issue. While programs designed to support and provide resources for Black women during and after pregnancy are crucial and highly important, they primarily serve as short-term remedies. These programs can help reduce symptoms but may not cure the underlying problem. To truly reverse the trend of unfavorable birth outcomes within the Black and African American community, we must focus on creating systems and environments where racism, microaggressions, and discrimination are met with a zero-tolerance approach.

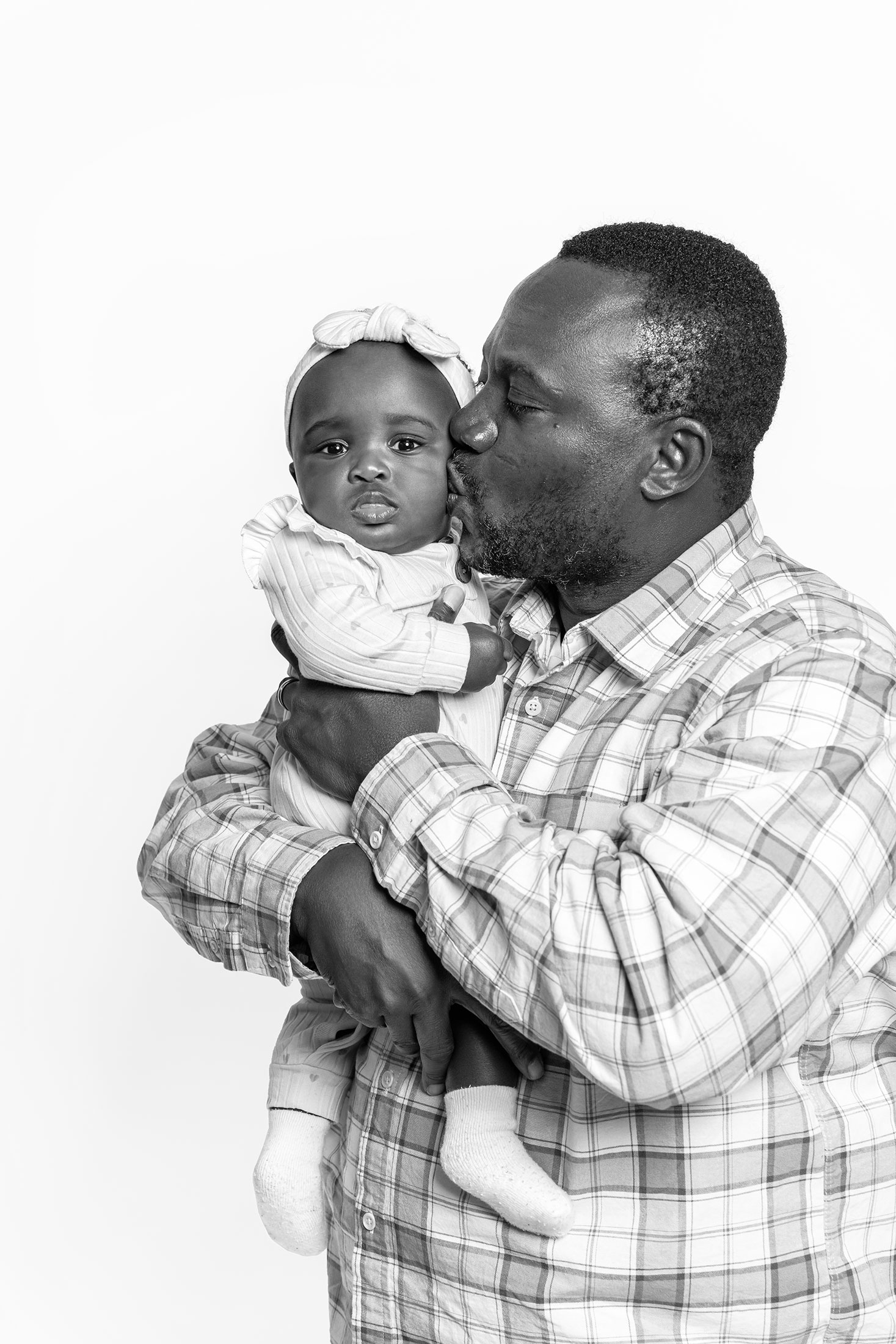

As a new mother to a beautiful baby girl, I want the best for her. I envision a supportive environment where she won’t have to worry about facing constant subtle racism and microaggressive reactions or remarks. For Black women, the chronic stress resulting from repeated exposure to subtle racism and microaggressions can lead to an increased allostatic load (i.e., the cumulative burden of chronic stress and life events), which may, in turn, negatively impact their reproductive health and contribute to poor birth outcomes.

This is the future I want for my baby girl and for the next generation of Black and African American women and their families — a future where they grow up in an environment that supports their well-being across their lifespan rather than exposing them to unnecessary stress that wears on their bodies. The unfavorable birth outcome epidemic is a crisis that demands the full attention and effort of everyone involved. We can and must, do better. By offering culturally sensitive healthcare, advocating for and implementing policies that address racial disparities, and consistently raising awareness about the influence of racism on health and well-being, we can work collectively towards a more equitable and nurturing future for all.